The first film by Agnès Varda that I saw was probably The Gleaners and I which is a good introduction to her style as she heartily embraced the newer and cheaper video technology to make films in a more personal way. When I saw Cléo From 5 to 7 it was surprising that I hadn’t heard more about it before. Then as I sought out and watched her other films I realized that she is one of the greatest filmmakers that we’ve ever had, pushing boundaries and working away for decades with a strong and distinctive voice. There is a trust and warmth that more explicitly came out as she was in front of the camera in her later films, but it was always there.

The first film by Agnès Varda that I saw was probably The Gleaners and I which is a good introduction to her style as she heartily embraced the newer and cheaper video technology to make films in a more personal way. When I saw Cléo From 5 to 7 it was surprising that I hadn’t heard more about it before. Then as I sought out and watched her other films I realized that she is one of the greatest filmmakers that we’ve ever had, pushing boundaries and working away for decades with a strong and distinctive voice. There is a trust and warmth that more explicitly came out as she was in front of the camera in her later films, but it was always there.

In looking through the statistics I’ve watched more films directed by Agnès Varda than any other director and every single one is enjoyable. With a career spanning seven decades she continued to explore, refine, and share how she worked. There are always fascinating people and places and cinematic techniques to learn from every time. With a deep curiosity and empathy Varda explored the world and the people around her. She paid attention to where people were, what they were doing, and what was going on around them and inside them.

With infallible instincts and a true genius for editing and framing, she truly was able to use cinema to help us understand each other more. With Varda’s cinema everything connects within her films and between them. As you watch more and more you will recognized people and places reappearing. Sometimes she points these connections out and sometimes she does not. The films are rewarding and the more you watch and rewatch the connections strengthen. It’s like living somewhere or with a friend who you find out more about as you share experiences and stories. Here are some cinematic highlights from some of the films she made.

An impressive feature debut filled with long and elaborately-constructed shots. The daily life of a French fishing village forms the backdrop for a couple who are breaking up. Much more of the film draws on the real inhabitants of the village along with many cats. It’s a blend of documentary and fiction that has all the later elements of her films and kicks off the whole French New Wave with some bold stylistic choices.

An impressive feature debut filled with long and elaborately-constructed shots. The daily life of a French fishing village forms the backdrop for a couple who are breaking up. Much more of the film draws on the real inhabitants of the village along with many cats. It’s a blend of documentary and fiction that has all the later elements of her films and kicks off the whole French New Wave with some bold stylistic choices.

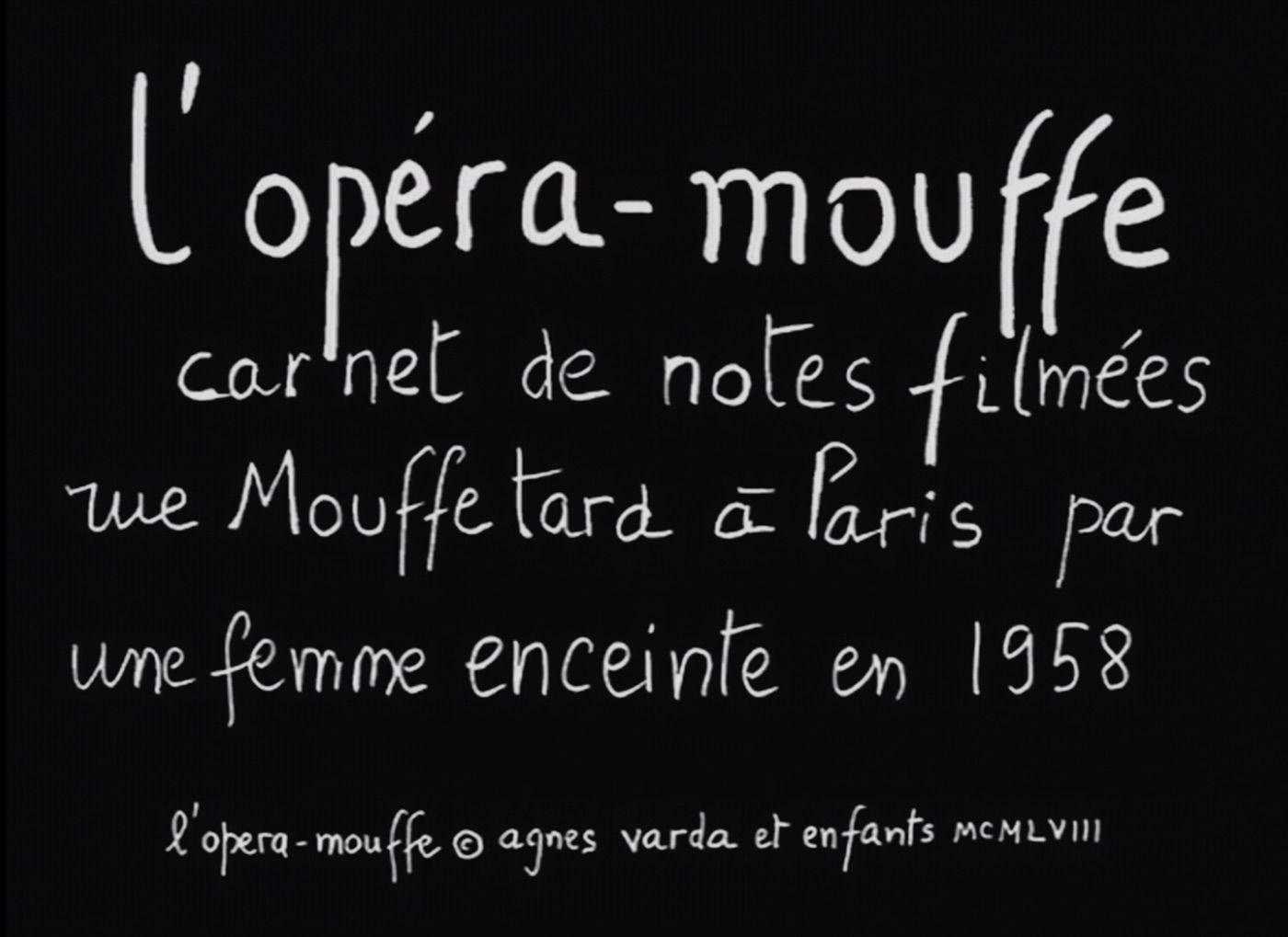

Made while Varda was pregnant with her daughter Rosalie, the short documentary / drama hybrid established her impressionistic style where the film connects things visually, sonically, and thematically. A reflection on a street and the people there, it deals with things both small and big in an innovative and experimental way that seems almost effortless. While documenting a street, it also playfully weaves in the relationship of a couple and a pregnant woman in a frank and delightful way. Still amazing and surprising in how far ahead of her time Varda always was.

Made while Varda was pregnant with her daughter Rosalie, the short documentary / drama hybrid established her impressionistic style where the film connects things visually, sonically, and thematically. A reflection on a street and the people there, it deals with things both small and big in an innovative and experimental way that seems almost effortless. While documenting a street, it also playfully weaves in the relationship of a couple and a pregnant woman in a frank and delightful way. Still amazing and surprising in how far ahead of her time Varda always was.

A stunning achievement from the first frame to the last with so much going on. At a simple level it follows a woman for two hours as she waits for the result of a cancer test. We follow in real time as the film changes location and tone with just about every possible combination of shot and style thrown in. It is the cinematic equal of Joyce’s Ulysses in how each section uses a different style to tell the next part of the story. It also manages to shift tone from light to dark within seconds or go from music to silence equally fast. As always, there are cats and mirrors and windows and real people and actors. It’s mind boggling how it fits together and works incredibly well. There is not another film like this and if it was the only film that Agnès Varda made we’d still be talking about it now, but this masterpiece is from the seventh year of a 70 year career.

A stunning achievement from the first frame to the last with so much going on. At a simple level it follows a woman for two hours as she waits for the result of a cancer test. We follow in real time as the film changes location and tone with just about every possible combination of shot and style thrown in. It is the cinematic equal of Joyce’s Ulysses in how each section uses a different style to tell the next part of the story. It also manages to shift tone from light to dark within seconds or go from music to silence equally fast. As always, there are cats and mirrors and windows and real people and actors. It’s mind boggling how it fits together and works incredibly well. There is not another film like this and if it was the only film that Agnès Varda made we’d still be talking about it now, but this masterpiece is from the seventh year of a 70 year career.

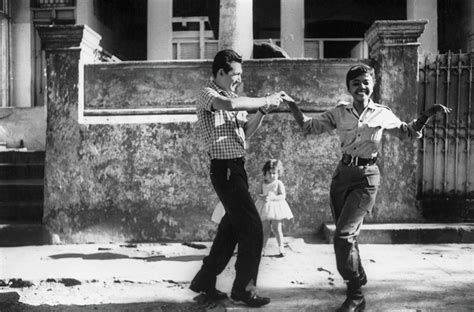

Constructed out of thousands of still images from a trip to Cuba, her 1963 film Salut Les Cubains is a playful history of the Cuban revolution and a snapshot of Cuban society. There is so much crammed into the short, but it never feels rushed. It’s a testament to her skill in drawing a story and connections out of disparate elements and weaving them into a way that makes it seem logical and comfortable.

Constructed out of thousands of still images from a trip to Cuba, her 1963 film Salut Les Cubains is a playful history of the Cuban revolution and a snapshot of Cuban society. There is so much crammed into the short, but it never feels rushed. It’s a testament to her skill in drawing a story and connections out of disparate elements and weaving them into a way that makes it seem logical and comfortable.

A colourful love story on the surface, but in reality it’s a brilliant satire of patriarchy. It depicts the wonderful life of a man married with children who falls in love with a younger woman who is a postal worker and then leaves his wife. The man is completely oblivious to the feelings of the women around him as it is all going on. Told with a subtlety and cognitive dissonance that shows skill and restraint, it’s one of the most sophisticated and biting critiques of films centred around the male gaze.

A colourful love story on the surface, but in reality it’s a brilliant satire of patriarchy. It depicts the wonderful life of a man married with children who falls in love with a younger woman who is a postal worker and then leaves his wife. The man is completely oblivious to the feelings of the women around him as it is all going on. Told with a subtlety and cognitive dissonance that shows skill and restraint, it’s one of the most sophisticated and biting critiques of films centred around the male gaze.

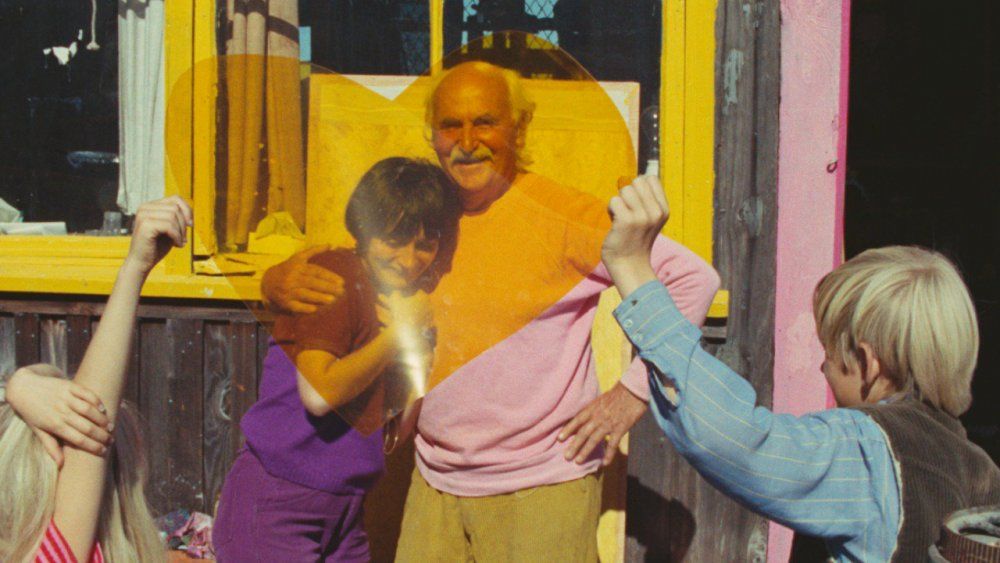

Varda and Jacques Demy moved to California for Demy to work on his Hollywood film Model Shop and Varda developed some fascinating films that were very much of the time and blended documentary and fiction. With Uncle Yanco she created a playful short portrait of a relative of hers who lived in a community made up of houseboats. It’s colourful and fun with Varda and the crew showing up all through the film.

Varda and Jacques Demy moved to California for Demy to work on his Hollywood film Model Shop and Varda developed some fascinating films that were very much of the time and blended documentary and fiction. With Uncle Yanco she created a playful short portrait of a relative of hers who lived in a community made up of houseboats. It’s colourful and fun with Varda and the crew showing up all through the film.

While in California Varda got to know the Black Panthers and created a timely documentary built around a rally to free Huey Newton in 1968. Through the members of the party she provides context for the struggle and the events of the time. It’s a compact and comprehensive history lesson that holds up incredibly well.

While in California Varda got to know the Black Panthers and created a timely documentary built around a rally to free Huey Newton in 1968. Through the members of the party she provides context for the struggle and the events of the time. It’s a compact and comprehensive history lesson that holds up incredibly well.

A feature film done with a studio and Varda’s first film in English. It’s a bit of a rambling shaggy dog story about three counterculture celebrities hanging out in their house in California. But as it progresses, the outside world starts to intrude and it starts to get surprisingly profound and meta. There are some great scenes with director Shirley Clarke playing a version of herself and a stunning sequence where she gets into an argument with Varda about her performance, so Varda puts on her costume and does the part of the scene. It’s a strange and unique late 60s film that is worth sticking with.

A feature film done with a studio and Varda’s first film in English. It’s a bit of a rambling shaggy dog story about three counterculture celebrities hanging out in their house in California. But as it progresses, the outside world starts to intrude and it starts to get surprisingly profound and meta. There are some great scenes with director Shirley Clarke playing a version of herself and a stunning sequence where she gets into an argument with Varda about her performance, so Varda puts on her costume and does the part of the scene. It’s a strange and unique late 60s film that is worth sticking with.

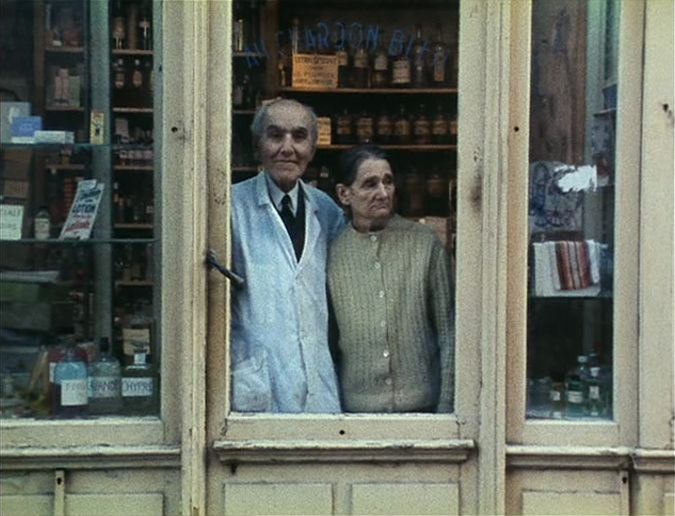

A feature-length documentary where Varda explores the street where she lived for most of her life. She visits many of the people there and links it all together with a magic show. Filled with lovely details and connections as people tell their stories and how it is all done with humour and empathy. In her neighbourhood of fascinating characters she shows how everything worked together by including moments that are specific, but also recognizable and universal. It exemplifies the approach that she seemed to take with all her documentaries in approaching people with openness and generosity.

A feature-length documentary where Varda explores the street where she lived for most of her life. She visits many of the people there and links it all together with a magic show. Filled with lovely details and connections as people tell their stories and how it is all done with humour and empathy. In her neighbourhood of fascinating characters she shows how everything worked together by including moments that are specific, but also recognizable and universal. It exemplifies the approach that she seemed to take with all her documentaries in approaching people with openness and generosity.

A 1970s story of the friendship between two women which provides a brilliant way to explore what the role of women is and was in the 60s and 70s. Bold in approach both in style and subject matter, it is fun and profound. Spanning two decades in the lives of the characters we see how their lives change as they define themselves, live their lives, and build careers. Dealing with the abortion debate in France as well as other rights for women, it’s passionate and sensitive. Skillfully weaving together drama and musical numbers, it’s a unique film that still feels relevant and vital.

A 1970s story of the friendship between two women which provides a brilliant way to explore what the role of women is and was in the 60s and 70s. Bold in approach both in style and subject matter, it is fun and profound. Spanning two decades in the lives of the characters we see how their lives change as they define themselves, live their lives, and build careers. Dealing with the abortion debate in France as well as other rights for women, it’s passionate and sensitive. Skillfully weaving together drama and musical numbers, it’s a unique film that still feels relevant and vital.

While in California, Varda was curious about the murals that she saw on buildings and that starts a journey where she meets some fascinating people. She gets the story of the murals, the artists, and the history embedded within the walls and the people within them and around them. It also provides somewhat of a preview of her later collaboration with JR in Faces, Places where she combined large outdoor art with small, personal stories. It exemplifies her ability to empathize and get people to drop their guard and share their stories with her. Some great insight into art, humanity, people, and Los Angeles.

While in California, Varda was curious about the murals that she saw on buildings and that starts a journey where she meets some fascinating people. She gets the story of the murals, the artists, and the history embedded within the walls and the people within them and around them. It also provides somewhat of a preview of her later collaboration with JR in Faces, Places where she combined large outdoor art with small, personal stories. It exemplifies her ability to empathize and get people to drop their guard and share their stories with her. Some great insight into art, humanity, people, and Los Angeles.

Blending drama and documentary, Documenteur tells the story of a newly-single woman in Los Angeles trying to figure out where to live and what to do with her life. Starring one of the editors of Varda’s previous film, Mur Murs, and Varda’s son Mathieu, it’s shot in a documentary style around Los Angeles. It’s a film that is impressionistic as we see a woman and her son building a new life in America. In some ways the structure and method of the film anticipates some of the approaches of the best of the mumblecore movement that would follow decades later.

Blending drama and documentary, Documenteur tells the story of a newly-single woman in Los Angeles trying to figure out where to live and what to do with her life. Starring one of the editors of Varda’s previous film, Mur Murs, and Varda’s son Mathieu, it’s shot in a documentary style around Los Angeles. It’s a film that is impressionistic as we see a woman and her son building a new life in America. In some ways the structure and method of the film anticipates some of the approaches of the best of the mumblecore movement that would follow decades later.

A drama about the last days of a young woman hitchhiking and living on the road. Constructed like a documentary and shot on location it’s uses an elaborate editing scheme and a non-linear structure to tell the story. Throughout the film some characters will address the camera or just look at it which adds to the unique blend of documentary and dramatic techniques. Stunningly shot with a series of tracking shots and with a memorable central performance from Sandrine Bonnaire, it’s a masterful character study of youth and alienation. We see how one person can affect the lives of others and a series of narrative threads connect in unexpected ways. Brilliantly mixing actors and non actors on locations, it’s a remarkable achievement in filmmaking filled with empathy, stunning compositions, and unforgettable characters.

A drama about the last days of a young woman hitchhiking and living on the road. Constructed like a documentary and shot on location it’s uses an elaborate editing scheme and a non-linear structure to tell the story. Throughout the film some characters will address the camera or just look at it which adds to the unique blend of documentary and dramatic techniques. Stunningly shot with a series of tracking shots and with a memorable central performance from Sandrine Bonnaire, it’s a masterful character study of youth and alienation. We see how one person can affect the lives of others and a series of narrative threads connect in unexpected ways. Brilliantly mixing actors and non actors on locations, it’s a remarkable achievement in filmmaking filled with empathy, stunning compositions, and unforgettable characters.

An odd, but surprisingly gentle film starring Jane Birkin as a woman who falls in love with a 14 year old boy. It’s an icky premise, but Varda manages to create an empathetic portrait that is complex with her own son Mathieu playing the boy and a young Charlotte Gainsbourg and Lou Doillon playing the daughters of their actual mother Jane Birkin. It also features Birkin’s actual mother and father playing Birkin’s parents too. Infused with 80s some video games and with the AIDS crisis hanging over everything, it’s about the characters, family, connections, boundaries, and the loss of innocence.

An odd, but surprisingly gentle film starring Jane Birkin as a woman who falls in love with a 14 year old boy. It’s an icky premise, but Varda manages to create an empathetic portrait that is complex with her own son Mathieu playing the boy and a young Charlotte Gainsbourg and Lou Doillon playing the daughters of their actual mother Jane Birkin. It also features Birkin’s actual mother and father playing Birkin’s parents too. Infused with 80s some video games and with the AIDS crisis hanging over everything, it’s about the characters, family, connections, boundaries, and the loss of innocence.

Made around the same time as Kung-Fu Master!, this portrait of Jane Birkin is playful and self-reflexive with Varda in dialogue the Birkin about how they are making the film. Filled with some elaborate scenes for Birkin to perform in, it’s a casual biography that gives both women the chance to flex their muscles and create memorable images and moments. In many ways it’s the beginning the phase of Varda’s career where she became more of a character and shared more of her own history along with the stories of others. It’s elaborate and complex and it all seems effortless, but it’s carefully constructed with deep levels of connection and insight throughout.

Made around the same time as Kung-Fu Master!, this portrait of Jane Birkin is playful and self-reflexive with Varda in dialogue the Birkin about how they are making the film. Filled with some elaborate scenes for Birkin to perform in, it’s a casual biography that gives both women the chance to flex their muscles and create memorable images and moments. In many ways it’s the beginning the phase of Varda’s career where she became more of a character and shared more of her own history along with the stories of others. It’s elaborate and complex and it all seems effortless, but it’s carefully constructed with deep levels of connection and insight throughout.

A loving, playful, creative, and moving documentary about the life of Jacques Demy, partner of Agnès Varda, and accomplished director. Made in the last year of Demy’s life as he was dying due to complications from AIDS, it skillfully blends clips, recreations, and footage of Demy into a comprehensive look at the development of a filmmaker and how the themes and visual motifs came from his life growing up. Using some of the same techniques from Jane B. by Agnes V., but taking it all to a deeper and more interconnected level, it’s one of the most cinematic portraits possible of a creative artist in how it extends, deepens, and contextualizes his work. I gained a whole new appreciation and love of Demy and his films after watching the documentary which made his films resonate much more with me.

A loving, playful, creative, and moving documentary about the life of Jacques Demy, partner of Agnès Varda, and accomplished director. Made in the last year of Demy’s life as he was dying due to complications from AIDS, it skillfully blends clips, recreations, and footage of Demy into a comprehensive look at the development of a filmmaker and how the themes and visual motifs came from his life growing up. Using some of the same techniques from Jane B. by Agnes V., but taking it all to a deeper and more interconnected level, it’s one of the most cinematic portraits possible of a creative artist in how it extends, deepens, and contextualizes his work. I gained a whole new appreciation and love of Demy and his films after watching the documentary which made his films resonate much more with me.

Varda assembled a huge number of film stars in the playful One Hundred and One Nights which has a loose narrative framework telling the history of cinema. Starring Michel Piccoli as Simon Cinema, it brings a string of celebrities (including Catherine Deneuve, Alain Delon, Jeanne Moreau, Robert De Niro, Harrison Ford, and Hanna Schygulla) to visit him as well as a student film crew who cast him in a film about cinema. A pleasant diversion that highlights some of influences of Varda over the years.

Varda assembled a huge number of film stars in the playful One Hundred and One Nights which has a loose narrative framework telling the history of cinema. Starring Michel Piccoli as Simon Cinema, it brings a string of celebrities (including Catherine Deneuve, Alain Delon, Jeanne Moreau, Robert De Niro, Harrison Ford, and Hanna Schygulla) to visit him as well as a student film crew who cast him in a film about cinema. A pleasant diversion that highlights some of influences of Varda over the years.

A more comprehensive overview of Demy’s work, but still with the same light touch. Moving around in time, it provides a history of Demy through the worlds that he created in his films. Some fascinating details such as how Harrison Ford was to be in an earlier Demy film, but the studio didn’t want him. Demy and Varda remained friends with Ford over the years which shows some of the personal connections that provided Varda with incredible access to people around the world. A great companion film to Jacquot de Nantes and a good way to figure out which Demy films to see as well as providing insight into the creative process and working in the film business.

A more comprehensive overview of Demy’s work, but still with the same light touch. Moving around in time, it provides a history of Demy through the worlds that he created in his films. Some fascinating details such as how Harrison Ford was to be in an earlier Demy film, but the studio didn’t want him. Demy and Varda remained friends with Ford over the years which shows some of the personal connections that provided Varda with incredible access to people around the world. A great companion film to Jacquot de Nantes and a good way to figure out which Demy films to see as well as providing insight into the creative process and working in the film business.

As technology changed and the DV revolution began to transform independent filmmaking, Agnès Varda picked up one of the cameras and started shooting. The cheap and portable equipment allowed her to work faster and fewer people and it resulted in her remarkable documentary The Gleaners and I. The central concept is that of the people who harvest discarded produce from fields. On a metaphorical level it’s a stunning look at how people exist in French society and how we relate to each other. At first the style seems meandering and almost random, but the connections keep happening, creating a deep and rich look at life in France in places and with people who are not usually featured in films. While the technology is new and exciting, the editing and organizational principles go back to Varda’s Diary of a Pregnant Woman from over 40 years earlier.

As technology changed and the DV revolution began to transform independent filmmaking, Agnès Varda picked up one of the cameras and started shooting. The cheap and portable equipment allowed her to work faster and fewer people and it resulted in her remarkable documentary The Gleaners and I. The central concept is that of the people who harvest discarded produce from fields. On a metaphorical level it’s a stunning look at how people exist in French society and how we relate to each other. At first the style seems meandering and almost random, but the connections keep happening, creating a deep and rich look at life in France in places and with people who are not usually featured in films. While the technology is new and exciting, the editing and organizational principles go back to Varda’s Diary of a Pregnant Woman from over 40 years earlier.

With The Beaches of Agnes she took a look at herself in a similar way to what she did with Jacquot de Nantes. Combining clips and elaborately staged scenes, it’s a joyful autobiography that filled with lovely moments and details as she reflects on her life. When I saw it I felt a bit melancholy as it felt like a final film or the last statement that she wanted to make. Using the metaphor of beaches and mirrors she manages again to make it all seem effortless as things connect and we move through time, emotions, and locations.

With The Beaches of Agnes she took a look at herself in a similar way to what she did with Jacquot de Nantes. Combining clips and elaborately staged scenes, it’s a joyful autobiography that filled with lovely moments and details as she reflects on her life. When I saw it I felt a bit melancholy as it felt like a final film or the last statement that she wanted to make. Using the metaphor of beaches and mirrors she manages again to make it all seem effortless as things connect and we move through time, emotions, and locations.

The only co-directed film in Varda’s career is Faces Places where she teams with up artist and filmmaker JR. They travel through rural France and set up huge photographic murals of ordinary people in the places they visit. Varda draws their stories out of them and makes all sorts of connections with them, JR, and her own work and history. In some ways it’s similar to much of her work and especially The Gleaners & I as it looks at people with a radical empathy that Varda infuses every frame with. It’s a lovely story of friendship, aging, and art that is profound and beautiful. As her penultimate film, it’s incredible as it is still complex with so much going on with never a false note.

The only co-directed film in Varda’s career is Faces Places where she teams with up artist and filmmaker JR. They travel through rural France and set up huge photographic murals of ordinary people in the places they visit. Varda draws their stories out of them and makes all sorts of connections with them, JR, and her own work and history. In some ways it’s similar to much of her work and especially The Gleaners & I as it looks at people with a radical empathy that Varda infuses every frame with. It’s a lovely story of friendship, aging, and art that is profound and beautiful. As her penultimate film, it’s incredible as it is still complex with so much going on with never a false note.

With the loss of Agnès Varda we say goodbye to one of the great modern filmmakers who used the medium in a personal and humane way to illuminate the human condition and to let us see the world from a different perspective.